Once a fire is burning, its behaviour is determined by three main factors: fuel, weather and topography.

On this page:

Fuel

Bushfires are fuelled by vegetation. How hot the fire becomes or how fast it spreads depends on the amount, type, condition, and the arrangement of the vegetation or fuels. For example, long dry grass, twigs and leaves will burn very quickly, while heavy forest and scrub will burn slowly but at a much higher temperature and at greater intensity.

By reducing the fuel load and creating a defendable space around your property, you can reduce your bushfire risk.

Different types of fuels

In South Australia, common fuel types include:

- grass usually after it is drying out or dead

- crops

- seaweed

- decomposing humus, peat and duff (fine ground litter)

- small shrubs and scrub (heath lands)

- plantation forest (eucalypts, pine trees)

- bush/scrub (eucalypts with under-storey vegetation, wattles, she-oaks).

Given the right conditions, most of these fuels will ignite and burn readily. All will burn with different degrees of intensity:

- Grasses respond rapidly to changing moisture in the air. Very dry grass (a deep gold and brown colour) absorbs moisture from damp air overnight which is lost to wind and dry air very early on high fire risk days. Grass fires can spread very rapidly.

- Scrub vegetation and trees drop leaves and twigs (fine fuel) on the ground around them. These fuels can accumulate in large quantities. This fuel burns slower than grasses, but gives off far more heat.

- When the bark on trees is fibrous and dry, flames from a surface fire can pre-heat and ignite the bark. This helps a fire climb higher up the tree, adding to both the height of the flames and the heat of the fire.

- When shrubs, branches and bark provide a continuous ladder of fuel up into the tree canopy, a bushfire can burn high in the trees and give off very large amounts of heat. This is called a crown fire.

Weather

Air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed and direction, and atmospheric stability can all affect bushfire behaviour.

Temperature

The hotter the air temperature, the less a fuel needs to be preheated to ignite.

Relative humidity

Humidity is the amount of water vapour in the air. Low humidity means the air is very dry as the lack of moisture in the air means fuels are drier and easier to burn. When humidity decreases to less than 30 per cent the fire danger increases as low humidity evaporates moisture from vegetation and flammable materials, making them easier to ignite.

On a typical summer day the air may contain very little moisture; it has a low relative humidity. This means that vegetation cannot absorb much moisture from the air. When the air is dry, the bush or grasslands are also dry from very early in the day, adding to the fire danger.

Wind

Winds will influence the speed a fire travels and the direction or growth of a fire when wind direction changes. Stronger winds can also carry embers and fragments of burning material, which can then light small fires ahead of the main fire front which are called spot fires. Wind can also be compressed and gain speed when rising through hills or gullies.

Strong winds are normally present during bushfires, which makes it harder for firefighters to bring the fire under control. The wind pushes flames closer to unburnt fuel and causes the fire to travel quicker.

In South Australia, winds are hottest from the north/northwest. Wind also dries out vegetation, making it more flammable, and bends flames over, allowing radiant heat to pre-heat unburnt fuel.

Wind influences:

- the speed at which a fire spreads. The higher the wind speed, the greater the fire danger

- the direction in which a fire travels and the size of the fire front. A change in wind direction will rapidly change the fire front and fire direction

- the intensity of a fire by providing more oxygen

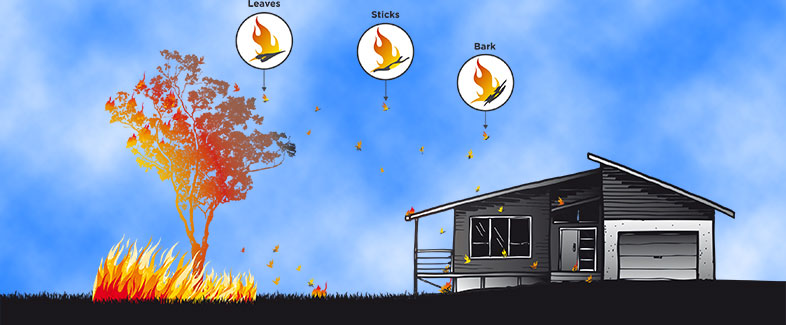

- the likelihood of spotting. Spot fires ignite when winds carry burning pieces of leaves, twigs and bark (embers) ahead of the fire.

Topography

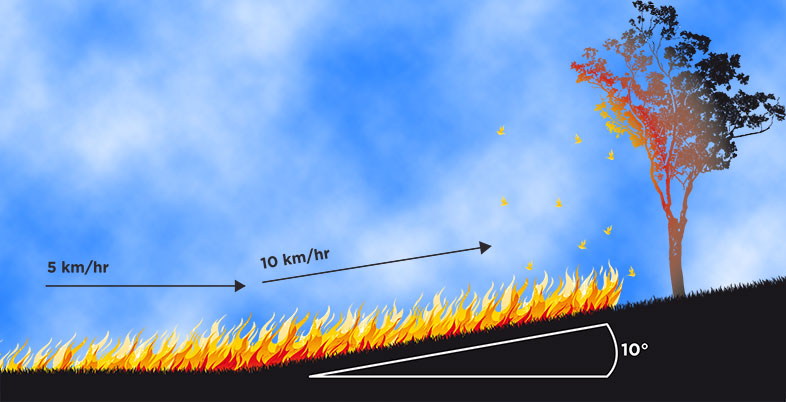

The topography, or shape of the land, has a strong affect on bushfire behaviour. As a general rule, the fire speed will double for every 10 degrees of lift. The opposite applies to a fire travelling downhill, with speed halving with every 10 degrees of fall.

A fire will burn faster uphill because the flames can reach more unburnt fuel in front of the fire, causing the fuel to burn more efficiently. The heat radiating from the fire pre-heats fuel on the slope ahead of the fire, causing the fuel to start burning more quickly.

The opposite applies to a fire travelling downhill: because the flames reach less fuel, there is less radiant heat to pre-heat the fuel ahead of the fire, so the fire travels slower.

How a bushfire spreads

Bushfires spread along the surface of the ground in three ways:

- Direct flame contact - flames touch unburnt fuels and raise their temperature to ignition. This process is hastened by wind blowing the flames deeper into the fuel ahead or an upward slope presenting fuel to the flames sooner.

- Radiant heat - radiant heat from the fire raises nearby fuel to ignition temperature, often before the flames reach it.

- Burning embers - when embers land on fine fuels, they can start small fires. If left unchecked, these fires smoulder, grow and spread. Winds carry embers ahead of the actual fire - sometimes several hundred metres ahead. They can land on flammable material, causing small fires to start.

Fires spread vertically from the surface through middle and upper-level fuels. Fires only crown into the tops of tall trees if there is fuel from the ground all the way up to the tree tops.

As a rule, flame height is between 3 and 5 times the height of the fuel. This makes cutting or grazing grass well worthwhile!

Fire is typically teardrop-shaped when there is wind. The back of the fire burns slowest, coolest and with the shortest flames. The fire front burns fastest and hottest and is the most dangerous place. The fire flank is also dangerous: in the event of a wind change the upwind flank will immediately burn at its maximum rate of spread.

Ember attacks

Embers are burning leaves and twigs carried by the wind, and can travel a great distance. Ember attack is the main cause of house loss in a bushfire, and can occur before, during and even after the fire front passes.